There is mention of bigamy in my novel What Empty Things Are These. I won’t say more about those details, since there may be one or two of you out there who haven’t read it. Hard to believe…. But there you are.

As I was saying: bigamy. While I was thinking up bits and pieces to put together to make my story, there was a story a-building in the press in Melbourne. It began with a simple and dreadful story of a baby being kidnapped from a baby pusher while her young and now frantic mother had her back turned. The search was immediate and determined. The constabulary looked high and low. Eventually, I think it was a passer-by who heard a child crying in a tumbledown shed somewhere, and there it was, the baby. They then found the two rather sad folk who had though he was so cute they had to take him home. The shed wasn’t home, by the way, just where they had eventually left the baby when it was clear the big search was on. Melbourne sighed with relief, tension gone. Back to coffee and cornflakes.

But that was not all, by any means. I’m not sure how or why the rest of the story got out, but eventually Melbourne was rivetted once more by the child’s family, as it emerged the baby’s father was, in fact, involved in the drugs trade. But that’s not all. You’ve guessed, of course. He also had another family other family in Sydney, and each entirely oblivious of the other.

There we are. That’s what happens when you start tugging on a thread.

Anyway, those of you have read WETAT know how this informed the novel. I thought it was a fascinating story and I could lay bets this was not uncommon in Victorian times.

And twas so, of course.

I went online to court notes from the Old Bailey of the time and there were quite a few of these tales. Incidentally, I also gleaned a fair idea of the layout of the court itself as it was then. Once more I confess I wrote this book based on research about London and not because I knew the city at all. Though I’m sure the relevant parts of the Old Bailey have changed since 1860.

It was an easy thing to do, to move around the countryside or between cities and remarry – or just move in with someone else. After all, how would you be traced? Identification documents were not what they are now, and photography was not common and really only for very special occasions. It would be an unlucky person indeed to be caught; there would have to be an unfortunate set of circumstances to lead to actual discovery. Maybe these people hadn’t moved very far.

In a review of Living in Sin: Cohabiting as Husband and Wife in Nineteenth-Century England by Ginger Frost, Dr Tanya Evans says:

‘The Judicial Statistics of England and Wales recorded 5,327 bigamy trials between 1857 and 1904 which averaged out at 95 per annum which Frost suggests made up about 1 in 5 of the proportion of bigamous relationships that probably existed. Judges and juries judged these unions as flexibly as communities and thought long and hard about particular circumstances before passing sentence. Most bigamists were treated leniently by the courts. In the later 19th century a minority spent over a year in prison while many, 25 per cent in the 1860s rising to 37 per cent in the 1890s, served less than a month’s sentence. Women sometimes left their first husbands because they were violent or because they needed to find somebody to support them and their children. Many individuals traded legality for happiness without losing sight of the concept or ritual of marriage and while continuing to use the labels ‘husband’ and ‘wife’. Subsequent unions were sometimes, but not always, more successful and happier than the first.’

This is all part of a larger picture, of course. While Adelaide and women of her class were painfully constrained in marriages with an outward image of strict rectitude, things could be a lot looser elsewhere. In fact, even amongst the middle class. The writer Wilkie Collins was rumoured to have two concurrent partners at one point. One of them left him when he was espe cially cranky with gout at one stage, got married and then came back (they say). So it could happen.

cially cranky with gout at one stage, got married and then came back (they say). So it could happen.

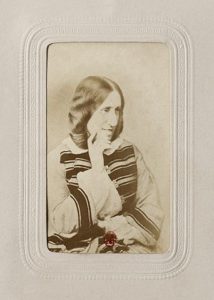

George Eliot, who was of course Mary Ann Evans, moved in with George Lewes, who was himself in an ‘open marriage’. George/Mary suffered somewhat from the approbrium of her class as a result – though Wikipedia says this may have been because she and Lewes decided to keep their domestics a secret. All the Victorian male middle class who had open relationships were mostly quite open about it. One suspects  the openness was not quite the option for women as it was for the men. There was, after all, quite a troope of moral police. And as we know, non-marriage and out-of-wedlock babies were not so recommended if you hadn’t the money or the support to carry it off.

the openness was not quite the option for women as it was for the men. There was, after all, quite a troope of moral police. And as we know, non-marriage and out-of-wedlock babies were not so recommended if you hadn’t the money or the support to carry it off.

All of this does make me think that we have our bourgeois Victorian antecedents for modern strait-laced habits. As I’ve said elsewhere, Victorian bourgeois were a bit sensitive about being filthy rich, and needed to demonstrate their worth by being terribly virtuous in the domestic sphere. So says Foucault, anyway. And also Judith Fleming, who points out that bourgeois Victorian houses were a showpiece of the family virtues.

In the meantime, the teeming masses were often enough not married at all, despite what novelists would have us believe. Who themselves, of course, were not always so strict about their own love lives.

There you are. Victorians did a great press, but you just can’t believe them.