Hold the presses – a very Victorian symbiosis

Years ago, I watched the very charming TV series of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford, that tale of a small community of the first half of the 19th century. I think it was in the second series where the ladies go for a ride on the train just newly arrived with its tracks in Cranford. They are rendered dizzy and quite breathless at the speed, which was probably about 15 or 20 miles per hour.

Why tell you this? Because the explosion in fast (it got faster) travel, along with the phenomenal growth in the middle class, urbanisation and education, meant an equally great explosion in print media. Journals, newspapers and books could travel to a new market (who could now read). By the early nineteenth century, there were 52 papers in London alone.

Victorians (those not otherwise occupied in cringing on the cobbles of heartless cities or down mines or coughing up the airborne fluff of factories) could read and argue about the expression of all sorts of political opinions. You could find the latest fashions. You could be horrified by war, famine and revolution. Finally!

Gone were the one- or two-page journals of the 18th century, with their tiny print-runs. By the 1850s, gone also was the onerous stamp and other taxes on publications – so you could also afford your news and rants.

The proliferation of publishing itself and, arm-in-arm with this, of journals, meant literature (from penny-dreadfuls with lurid covers to the very thoughtful Trollope and George Elliot) also hit the sun. Fame at last! A living at last! Sudden interest in the pursuit of copyright!

In fact, authors soon found you could earn an almost decent living through serialisation in journals. Which explains a little something – if you were wondering why Victorians could be so long-winded. They were, of course, paid by the word. I myself put this together in my head and concluded that 2+2 adds up to quite a lot. This is where I decided that a Victorian voice to my novel What Empty Things Are These need not necessarily entail half-page sentences. You’ll be glad to know or you will already have discovered.

And of course, ‘even’ the ladies could take part in the conversation on social issues and politics, art, philosophy, country rambles. And they could do it as writers! Very early on in the century, Mary Russell Mitford’s Our Village sketches were published in The Lady’s Magazine before being published in book form four years later. Her many and various writings helped support her family… and also illustrate how literary publishing crossed over with journalistic publication for much of the century.

At the other end of the century, Flora Shaw (Lady Lugard) wrote for the Pall Mall Gazette and the Manchester Guardian, having already been an oft-published author. Though she was not, it must be said, a very radical thinker.

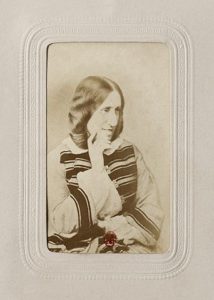

In between, women found all sorts of means of expression (and a bit of money) from the existence of an active press. The list of this rash of women novelists is long. They spoke of the world and their place in it, of psychology, of the relations between people, morals, religion and on and on. And this even though the usual preconceptions about women persisted – Elizabeth Gaskell had a large audience for her views on the repression of the working class, as well as quite a few sneering male detractors.

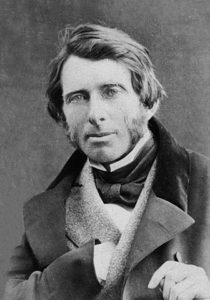

But I digress. Dozens of journals were born in 19th century Britain, many of whom continued to exist for decades; some of whom continue to exist today. They carried prevailing political views, they were a vehicle for new thoughts. Ruskin, a major thinker of the time, not only wrote about art, but also about geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and political economy. His pre-socialist views lit up the pages of, amongst other journals, The Cornhill Magazine, which published his series of essays entitled ‘Unto This Last’. In my novel, Adelaide sends off her work to Mr Thackeray, The Cornhill’s editor.

And of course, writers incensed at the parlous state of the very poor could say so. Dickens did just this; Wilkie Collins popularized the precursor to the thriller and also incidentally helped spread the conversation about women’s status, as well as other issues such as mental health; and Margaret (Mrs to you) Oliphant extolled the domestic, the historic and the supernatural.

Some, such as Margaret Braddon, Dickens, Huxley, Thackeray, Trollope and Ellen Wood decided to ensure a paying career by creating, supporting, and editing periodicals to publish and circulate it widely before book publication. Ah, what we writers have to do! From the early nineteenth century, too, bulky journals appeared called ‘reviews’ which kept the ardent novel-reader abreast with the latest being published.

A vastly different time, yet… not so much. The proliferating crowd of writers had to find some means of promoting their work and thus spent a lot of time in finding a creative way of doing so. Seems familiar. Just saying.