The society of women (some thoughts)

This month, I’m continuing with the theme of women in 1860 (or thereabouts), and their relationship with each other. It’s a not-so-subtle, and not at all minor, sub-theme in What Empty Things Are These (or WETAT for short). And you will recognise references to the book… which you have (of course) read.

I have a view that within any overarching culture there are sub-cultures – there is a male (masculine) and a female (feminine) culture which exist within the whole, for example. The more complex the society, of course, the more I am sure we could spend many happy hours identifying all sorts of other sub-cultures. There’s class, of course, and most obviously. And the male and female cultures, logically, also include and are influenced by class.

Picture if you will those Venn diagrams from high school, and imagine a number of overlappings. You will need a couple of hours, paper and coloured pencils. Come back when you’ve finished.

And you will all of course be perfectly aware that notions such as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ are imposed cultural things and do not relate closely if at all to scientific and psychological definitions of male and female, or, as they are otherwise known, ‘people’. We come from neither Mars nor Venus. I just thought I’d get that one out of the way. Everybody passed that one with flying colours, of course.

And so we return to Adelaide and Sobriety in WETAT, speaking of women and class. These two are, of course, separated by their relative status. Yet they share a close proximity, and an intimacy – when you come to think of it – over and beyond that of most women. There’s a companionship implied in being a lady’s maid; though not every woman, maid or mistress, would necessarily have enjoyed the fulness of that role. I imagine the better and more satisfying the mistress’s social life, the lonelier the maid. And a lady’s maid, after all, didn’t mix with Downstairs staff, by and large, and separate duties separated her from the housekeeper (supposing the household supported such a large staff in any case). Still.

There’s a companionship implied in being a lady’s maid; though not every woman, maid or mistress, would necessarily have enjoyed the fulness of that role. I imagine the better and more satisfying the mistress’s social life, the lonelier the maid. And a lady’s maid, after all, didn’t mix with Downstairs staff, by and large, and separate duties separated her from the housekeeper (supposing the household supported such a large staff in any case). Still.

Still, and despite the startling arrogance of a trend amongst the 19th century ladies-of-the-house always to refer to their lady’s maid as ‘Mary’ (Adelaide’s sister-in-law, Mrs Courtney, does that, you will recall) this didn’t hold for all. And even where it did (and I suppose we must accept that many bourgeoises of the 19th century were a bit obtuse about respect as we would see it now), still it is true that maid and mistress were thrown together and frequently developed a very close relationship.

Sometimes, indeed, the relationship was so close that maid and mistress each came to refer to the other by her first name. This in a society where formality was such that ladies of decades’ acquaintance could refer to each other as ‘Mrs Whatever’ until death finally separated them. It’s only been two or three generations since that formality died away.

Adelaide, however, had few friends of her own. Sobriety’s family were far away, except for her sister who had died of cholera. And they were of an age.

It’s this and other elements in her life that prompt Adelaide to begin her written musings on the relationship of women to each other and across class. Add to this influence, of course, that of literacy, which was by 1860 spread across a much-expanded middle class and carried to a working class (whose one day off a week had been commandeered by worthy charitable groups to ensure they could read the bible)… and you have the ability for people from different classes to share information, the events of the world and each other’s point of view.

Women, in this more literate world, had the full range of journals open to them, including journals featuring fashion.

Ah, fashion! I wrote an awfully long appendix about fashion and fashion plates in 1860 for my thesis. And it did creep into another blog of mine. I know, I know. But there’s a lot to be deduced from fashion and the way it’s represented. I won’t go into all of that here, and those who are still standing/awake after this improving chat can always have a look at the thesis itself.

Anyway. Fashion plates had properly come into their own by 1860, were tinted in lovely colours and everything.  The plates themselves had a pervasive influence on the times – fashions themselves would, since you couldn’t just keep presenting the same frock pattern ad infinitum week after week, begin to change more rapidly; women across classes would begin to be influenced by the same or similar fashions; and, more subtly, women would become more conscious of themselves as a group.

The plates themselves had a pervasive influence on the times – fashions themselves would, since you couldn’t just keep presenting the same frock pattern ad infinitum week after week, begin to change more rapidly; women across classes would begin to be influenced by the same or similar fashions; and, more subtly, women would become more conscious of themselves as a group.

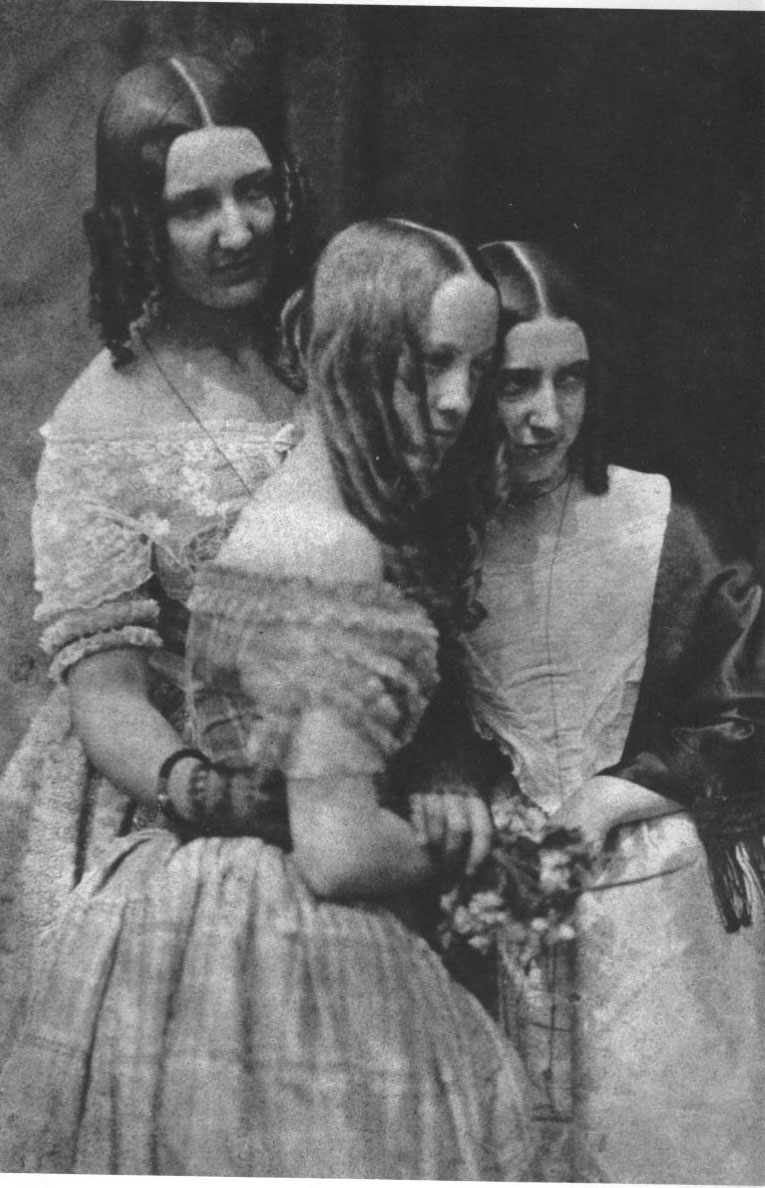

Fashion plates of the time presented women, each wearing a variation of the fashion being promoted, in pairs or in groups. Not, it must be said, depicted as guffawing at a private joke or diving into champagne – rather, they were always rather cool and aloof with each other. After all, docility was required of ladies. Still, there they were, in their pairs and groups, clearly sharing a social life of some sort.

I find this interesting on a number of levels. That, firstly, it was an expression of women as a group interested in the life of the group and in each other. Women looking at women. Secondly, I can’t help but remember all those times over the many decades since then when it was stated that women just don’t like each other and are just so deeply nasty… when, all the while, it’s men who continue to use various forms of psychological attack to drive women from employment in various sectors from journalism to scientific research. Just saying.

*Fans self.

Sorry, I digressed.

The notion of fashion in 1860 (and any era since) ties in with sexuality and sensuality too, of course. As I have said in that other blog. After all, fashion advertises the female shape-du-jour, which itself implies sexuality while, conversely, putting real sexuality at a distance because it’s been dressed up and turned into stereotype. Or caricature, if you think of the hourglass shape.

Then there is sensuality implied by the materials themselves, how they would look and how they would feel (Sobriety, it amused me to write in WETAT, reflected the dour Methodist sub-section of her class by doggedly removing every flounce from the dresses that Adelaide handed on to her. As a servant too, she would be very conscious of her status and therefore not prone to drawing attention with too many added extras).

Thus, it’s very arguable that then, and now, a certain level of the homoerotic is implied in fashion plates because, after all, it is women looking at women. Yet, yet, yet.  While this is true, I do think it must never be forgotten that men, by implication, were and are somewhere in the background. We are conscious of each other, and we are conscious of them. Women were enacting a role which was required of them; and clothes were an expression of what the men could afford to wrap their women in. Ruskin, after all, ranted on about extravagant dress because it was, at its extreme, about the parading of wealth. Men’s wealth, of course.

While this is true, I do think it must never be forgotten that men, by implication, were and are somewhere in the background. We are conscious of each other, and we are conscious of them. Women were enacting a role which was required of them; and clothes were an expression of what the men could afford to wrap their women in. Ruskin, after all, ranted on about extravagant dress because it was, at its extreme, about the parading of wealth. Men’s wealth, of course.

Nonetheless, the notion of women as a culture of their own within the broader culture is an interesting thought. While those guys were indeed always lurking and always an influence, women related to each other in distinct ways that were fundamental to society but at the same time ignored for their importance.

Quietly, some barriers broke down simply because of intimacy and proximity (Adelaide and Sobriety, for example). But on the other hand there was also the society of class, family and the domestic sphere, all held together by women: in WETAT, Adelaide’s fearsome sister, Gwendolyn, dictates the mores of her family of siblings and their children. She is the moral gate-keeper; while she is isolated, in fact, by her very position of authority, nonetheless her sense of self is derived from it. She also, represents the fiercer aspect of mistress as gatekeeper – not someone any servant (or relation) would want to cross, really.

Meanwhile, Adelaide’s house itself hums as a kind of hub of women, whose work keeps up appearances for the bourgeois family, to be sure, but whose relationships and the lines between them begin to blur and reshape as the patriarch’s influence wanes.

Interestingly, the bypassing of women’s society by history is to miss entirely that there was a society of women, operating within the whole. And that the humming of that women’s society in every household was deeply influential.

These have been some notions, only, on some aspects of the social history that was and is women’s. I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Next month I’ll start to look into the wild and occasionally murky world of Victorian entrepreneurism and, well, corruption. What a time it was!