Of fraudsters and their hired thugs

Ah, my friends, you’re back. I promised you a look at shonky Victorians who took advantage of burgeoning capitalism and the leap to the fore of intrepreneurialism … and inspired a major character in my book, What Empty Things Are These. So did The Way We Live Now, by the wonderful Anthony Trollope, writing a little later than my period of 1860.

Here it is.

As an adjunct, and before we dive into the tales of two men who successfully rorted the system (such as it was) I might mention the Irish. Here we had, for all of you who remember your history, a demographic reviled by the British in the time-honoured way of the powerful. After all, if you revile your victims, you don’t have to feel sorry for them.

Anyway, the upshot of appalling treatment of the Irish by their English landlords and their best Anglo-Irish mates was, in the end, the Great Famine. This, we all know, has been described by many more as a natural disaster, along the lines of ‘those poor potato-eating fools, killed off because their mono-agriculture went bad.’ Well, yes, it did indeed go bad. Irish tenant farmers had very little, and struggled to produce cereals for their landlords and also feed themselves. Potatoes were easy and cheap to grow, especially a couple of high-yield types. Everyone became reliant on them, but of cour

se growing one or two types of one kind of crop makes the crop very vulnerable to disease. When the blight came along, Ireland was devastated.

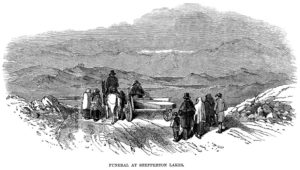

But there was never a necessity for this: during the whole of the famine, foodstuffs of all sorts continued to be exported by the shipload, and people continued to be evicted from their poor homes. Some in the British Parliament had some sympathy, but others simply did not and left the onus of relief up to local landlords. Whether these landlords were unable to help because of cost, or just didn’t much want to help at all, depends on who you read. Those who couldn’t pay their rent were likely to have their cottage destroyed rather than be allowed to continue to live in them. Freezing to death was a definite possibility for many.

About a million people died from famine and from diseases such as typhus linked to starvation.

Why mention this? Well, remember that the famine took hold in the mid to late 1840s, and that the upshot of it was that Irish people left the country in droves. Ireland’s population still hasn’t recovered. Some of these droves went to England. The fictional Mr Spillane of my novel was one who, among non-fictional others, were employed as thugs by the shonks of the intrepreneurial world of mid-century. If you want thugs to control your disappointed investors, not to mention others who might give you bad press, employ desperate people who are beyond caring what they do in order to eat.

No doubt, and to be fair, there were some shining souls who were as honest as the day is long and really did carry their happy investors along with them as they developed, say, new railroads and other boons for an enraptured public. Otherwise, there wouldn’t have been railroads and so on – though remember that even in the best of circumstances and totally up-front practices, those working on the railroads (‘navvies’) lived in appalling conditions and could expect no compensation for themselves or their families if anything went wrong, as it often did. Their pay was meagre and subject to fines for little infractions that could be concocted for the purpose. Not surprisingly, many navvies were Irish.

But I digress…

And so to our samples of entrepreneurs of the least savoury sort.

The Railway King

George Hudson, a farmer’s son who went on to impress as a draper, was left an impressive £30,000 by a relation in 1827. He sallied forth into investment, was successful as a shareholder in the North Midland Railway, and then established his own railway company to link York with towns in the West Riding. All good – the railway was in fact completed in 1839, after a reasonably stupendous £446,000 was raised for it.

After this success, the noble George invested in the Great North of Engla nd Company, to enable the completion of its line to Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Permissions were required by the House of Commons apparently – so it wasn’t as though there were no oversights whatever. George paid out over £3000 in bribes and successfully got over any objections.

nd Company, to enable the completion of its line to Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Permissions were required by the House of Commons apparently – so it wasn’t as though there were no oversights whatever. George paid out over £3000 in bribes and successfully got over any objections.

From there, George formed the Midland Railway Company and raised £5,000,000 (an eye-watering sum at the time). He personally guaranteed that 6% would be paid in dividend.

What with one thing and another, George’s companies controlled 1,016 miles of railway track by 1844, which earned him the title of ‘the railway king.’ He was, not surprisingly, also active and influential in politics, and was elected as Conservative MP for Sunderland in 1845, after having held office as councillor, alderman and lord mayor. Equally unsurprisingly, he argued with great vigour in the House of Commons against government supervision of the railway system.

He continued to buy shares in railway companies, though later it was found not all of his share-dealings were entered in the books. For a time, he was mates with George Stephenson, renowned engineer and inventor and probably an upstanding and honest fellow. In any event, though they worked together on many projects, Stephenson grew suspicious of Hudson’s methods by 1845, and resigned from the board Hudson’s York and North Midlands line.

Not to worry. George linked himself up with the Duke of Wellington, made him a heap of money and received in return much kudos to elevate him from the onus of an ordinary social background.

Soon, he discovered the benefits of insider information to manipulate share prices. For a while, this was very profitable. But prices were becoming inflated and soon crashed. Those who had trusted George now found financial disaster looming. Hudson was forced to resign as chair of all of his railway companies. An investigation found he had lied to investors and bribed MPs. He had even sold land he did not own. He agreed to pay back the money he had swindled.

His punishment, however, did not include having to resign as MP for Sunderland. He hung on there until 1859, though it will not come as a shock that he could not pay all that he owed, and was imprisoned for debt in 1865. He still had friends though, and these raised enough money to have him released in 1866. He died in 1871.

‘Baron’ Grant

Abraham Gottheimer was the son of a poor Jewish pedlar and immigrant, Bernard Gottheimer. Bernard did well in the business of the importation of fancy goods. Abraham received a good education, and – like George Hudson – sought to ditch his low-status backgound. In this case, it was by assuming another name, Albert Grant, just before he got married in 1856. He was at this stage a clerk and then a travelling salesman.

It is unclear to me where Albert’s first batch of investible money came from. Perhaps his father had done very well indeed, or perhaps his wife, Emily, came with a bonus. In any case, Albert was able to start his career in the establishment of companies in 1859.

The first of these was the Mercantile Discount Company, which collapsed in 1861. All undaunted, Albert established exotic-sounding ventures such as the Central Uruguay Railway, the Belgian Public Works, the Cadiz Waterworks, the Labuan Coal Company… and then the Crédit Foncier and Mobilier of England, which was useful in launching a number of other ventures. He was quite ruthless in his methods of courting investors, and made a point of smoozing clergymen and widows in particular. They handed over their mites most enthusiastically. The companies he established between 1864 and 1872 all collapsed in a welter of accusations of fraud against Albert. He too, of course, promised enormous dividends that he doesn’t seem to have ever intended to give over.

All of this he managed while promoting himself to the good electors of Kidderminster. Despite loud rumblings against him and his business methods, Albert found a couple of enthusiastic referees to vouch for his character, and so became the Conservative Member for Kidderminster in 1865. He didn’t stand in the general election three years later.

Ever busy on his own behalf, Albert somehow acquired a hereditary baronetcy from Victor Emmanuel II of Italy in 1868. This was said to be a reward for his services to the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in Milan, but was perhaps more due to the dextrous use of bribery in some form. Though people still shouted themselves hoarse about things like dishonesty, in 1872 the baron got himself made a Commander of the Portuguese Order of Christ as well.

All undaunted by rumour, the Conservatives put our baron up for election again in 1874, again in Kidderminster, and he won by a hair’s breadth. By now, however, his detractors were truly vocal, and allegations of corruption (including bribery of voters) came forth. They said that 40 to 50 public houses had given free drink to people wearing Conservative colours and willing to be listed as supporters of the noble Albert. The baron protested of course, but then it was found that his expenditure was roughly three times what he had declared. The petition against his election was successful and he was unseated.

Less subtle about his frauds and possibly with fewer friends than had George Hudson, the baron was constantly in court over his debts from 1876 until he died. There was even a foreign debacle where he was found to have been involved in the fraudulent sale of shares in an already-exhausted mine in Utah. Though declared a bankrupt, he valiantly attempted a resurrection by establishing a new bank in 1878, but that failed too. Once again he was declared a bankrupt. He died in 1899, in poverty, and his personal property was sold up.

—-000—-

And so there you have it. If you were lucky and very, very good at your research, you probably could have made a tidy profit as a small investor in Victorian Britain. If you had no idea what you were doing, things were likely to end badly. Yes, I know. This all sounds very familiar.

They were, after all, our immediate ancestors both personally and culturally.