At last, the blog about Victorian feminists, I hear you say! Well yes, by 1860 in Britain there was indeed a nascent feminist movement, the direct consequence of the rise of the middle class, the supremacy of urban life, education, the explosion in the printing industry and a few other social and economic revolutions.

I suppose people can, and will, argue with me about what caused what – but it remains true that women became aware of themselves in the Victorian era much more than they had done before. This was the political hinterland to the movement that brought about votes for women. I think it can safely be said that great revolutions have long beginnings. And even for this hinterland, there was a hinterland…

I’d add as a catalyst for feminism the rise of the nuclear family, too. It seems to me there was a lot of impetus for women to support themselves, since when the support of the direct family falls apart, it does so spectacularly. There was, after all, no social security. See, for example, Adelaide’s situation when George has his stroke. The choice between genteel poverty and escape from the mire raised its head. And it didn’t help that the extended family proposed her absorption, either.

Those of you who have read What Empty Things Are These will know what I mean. The others might consider buying it to find out. Just saying.

But my fictional Adelaide isn’t, of course, the only example. Mary Russell Mitford supported her family by writing; as did Margaret Oliphant. There was the occasional female journalist, and quite a lot of crossover between literary and journal writing.

This was the meeting point between ‘needs-must’ and opportunity, of course. Here were middle class women who needed to survive, who had no bloke or close rural community to support them, and finally here was the means (however limited) as well.

But this wasn’t all that was going on. Urbanised and gentrified society does do one major thing (among many) – it assumes a certain amount of education, it produces a certain amount of leisure, and it gives space for a lot of discussion.

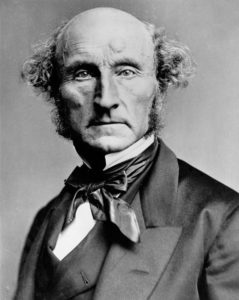

Among the major commentators of the time was John Stuart Mill, of course, who deserves accolades and honour for being a feminist well before this was common among men. If it could be said to be common even now… All he had to do was follow the logic, really. He discoursed governance, about liberty and equality, and about women. Bless him. He said in his The Subjection of Women:

‘[N]o one can safely pronounce that if women’s nature were left to choo se its direction as freely as men’s, and if no artificial bent were attempted to be given to it except that required by the conditions of human society, and given to both sexes alike, there would be any material difference, or perhaps any difference at all, in the character and capacities that would unfold themselves.’

se its direction as freely as men’s, and if no artificial bent were attempted to be given to it except that required by the conditions of human society, and given to both sexes alike, there would be any material difference, or perhaps any difference at all, in the character and capacities that would unfold themselves.’

He also, even without the aid of Marx (who had yet to make himself felt) noted that the rise of the middle class, with its emphasis on equality (well, shall we say more so than the previous regime of aristocrats, merchants and peasants, perhaps), made the continued oppression of women all the more obvious.

Of course, the Victorian era was marked by, well… Victoria, the queen, who, alone among women, had no legal restrictions on her at all. To a degree, this may have had an effect on the times and on views of women, but you might not want to put too much emphasis on that. After all, Elizabeth 1 was a mighty royal too, but made not a lot of difference to the lot of women as a whole.

However, perhaps people got used to the sight of a woman at important occasions of state. Who knows.

But it is a fact that women whose families had treated them as people as they grew up began to itch to be recognised as more than a clothes-horse or domestic worker or ornament. We know that by the turn of that century, women like Emmaline Pankhurst had come to decide that nothing less than a role in government and elections would do, since it was patently obvious that women were unrepresented in all-male government.

But Pankhurst’s predecessors had already begun to battle their way into the marketplace. And no easy feat was that.

Even nowadays, we sometimes hear the stories of women having to withstand the abuse of men in their attempt to elbow their way into traditionally-male sectors such as technology or even some of the sciences. Imagine, if you will, what it must have been like to turn up daily to your studies in law or medicine, as the only woman in a sea of black jackets and ties, smirks and innuendo!

But, until the late 1840s, there was no such thing as higher education for women. Why bother, after all, when women were handed as property from father to husband, who could beat them legally (though not actually kill them). John Stuart Mill described the condition of women in Britain – from the middle class to the appalling conditions of women working in coal mines – as slavery.

Yet things were changing. Caroline Norton was married to a cruel man in the 1830s, but was able to raise a national campaign for reform of divorce laws, and gained legal changes that would allow a woman to be rid of a cruel, adulterous or neglectful husband. Not, it should be said, that divorce was easy for women even then. Change is always slow and difficult when it comes to societal preconceptions.

In fact, Australians will be surprised to learn that Britain is only just considering, in 2019, the introduction of no-fault divorce. I know!

Norton’s major landmark achievement was to bring about (with the help of male supporters within parliament) the Infant Custody Act in 1839. Once again, it was limited – if divorced but not found guilty of adultery, a woman could have custody of any child under seven – but it was a far cry from the assumption that children were automatically the husband’s property. Sadly for her, only one of her children was young enough to be covered by this, and her husband took the children off anyway, to where the law did not apply in Scotland. When her youngest died of lockjaw in 1842, she was finally allowed custody of the other two for half of each year. She’s here on the right, in 1832.

Norton’s major landmark achievement was to bring about (with the help of male supporters within parliament) the Infant Custody Act in 1839. Once again, it was limited – if divorced but not found guilty of adultery, a woman could have custody of any child under seven – but it was a far cry from the assumption that children were automatically the husband’s property. Sadly for her, only one of her children was young enough to be covered by this, and her husband took the children off anyway, to where the law did not apply in Scotland. When her youngest died of lockjaw in 1842, she was finally allowed custody of the other two for half of each year. She’s here on the right, in 1832.

The campaign for improvements to divorce law continued, of course, as did campaigns on property rights. Barbara Bodichon was a leader in this, during the 1850s. There was opposition, and attempts to sideline changes in parliament, but finally divorce itself was made more widely available in 1857. The clergy weren’t pleased at all, but the whole idea was massively popular and the divorce rate soared by about 300% in 1858.

In the meantime, women and some men had banded together to found colleges of higher education for women. Interestingly, one of the supporters of this springing-up was Charles Kingsley, whose daughter Mary, born 1862, was an ethnologist, scientist and writer, and as an adult set off to explore Africa dressed – as you do – in muttonchop sleeves and boots, and armed with an umbrella.

Anyway, these women’s colleges had their effect, and by the 1870s colleges in the ancient universities began to offer something close to a university education to women. Cambridge, however, refused to award degrees to women all the way up to 1948.

Do we resent this? Of course we do.

Women were doing it for themselves and also, crucially, helping each other to do it. Feminists of the 1850s, 60s and 70s included Emily Davies, who escaped a life of needlework and met two other inspiring women: Elizabeth Garrett, who became Britain’s first female doctor, and Barbara Bodichon (pictured on the left), already making her name in the campaign to change divorce and property law. These women worked with other similarly focused women; Elizabeth Blackwell was an Englishwoman who had become the first female doctor in the United States and came back to Blighty to help the cause.

Women were doing it for themselves and also, crucially, helping each other to do it. Feminists of the 1850s, 60s and 70s included Emily Davies, who escaped a life of needlework and met two other inspiring women: Elizabeth Garrett, who became Britain’s first female doctor, and Barbara Bodichon (pictured on the left), already making her name in the campaign to change divorce and property law. These women worked with other similarly focused women; Elizabeth Blackwell was an Englishwoman who had become the first female doctor in the United States and came back to Blighty to help the cause.

You can see how things grew, particularly since the ground was fertile. Work by Garrett and Davies in the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, in persuading London University to award degrees to women, and towards the recognition of women’s qualifications in teaching led to a proliferation of change. Davies was the first woman to ever appear as an expert witness before a royal commission in education.

Much of this work, it’s reasonably obvious, mostly affected middle-class women, it’s true. Still, all women suffered from restrictions on employment deemed suitable for them, so the working class was not forgotten. In fact, the attention slowly turning to the plight of women led to protections for women in particularly noxious forms of work, such as in mines. Domestic servants however – and most of these were women – drudged on until the social upsets of the post-WWI virtually eliminated the domestic sector from all but the wealthiest of houses, starting their employment as children and enduring even longer hours that factory workers.

Look, I could go on forever. Suffice it to say that where we are aware of the suffrage movement for women in britain and elsewhere in the West at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, change was happening through much of the hundred years before that, due to a lot of determination and the weathering of a lot of withering sarcasm.

A hundred years before the suffrage of women, I hear you say? Yes indeed. Don’t forget, after all, that Mary Wollstonecraft – Mary Shelley’s mother – wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1798.

It’s been a long haul.