Victorian children in Britain didn’t have wardrobes and chests full of toys and games, in general. There was none of that blinking, blurping buzzing stuff on phones and games sets that they have now. Land sakes, even I made up some of my own toys and games when I was a gel, born 90 years after Adelaide Hadley was wondering what to do with her life!

(Adelaide Hadley is the main character in my novel What Empty Things Are These. If you haven’t read it, I will smile a little sadly until you do.)

Now, where was I?

Ah yes. The little Adelaide, playing in around 1850 or so, was keen, you will recall, on making dolls out of clothes’ pegs:

‘I collected candle stubs and matches, snippets of wool and material from Mama’s sewing box, and clothes’ pegs that

I turned into well-dressed dolls, pasted with flour-and-water stirred together in the kitchen. They wore tiny

curling feathers in their headdresses.’

Had she not been doing this in her hiding space under the stairs, she might have been playing with one of those astonishing dolls’ houses Victorian girls of the richer variety were given. Admittedly, these existed, so they claimed, specifically so that little girls could learn about domesticity and generally how to a house. Toys, after all, must have an educational value. I’m sure every rich little Victorian girl kept this very much in mind while rearranging the furniture in her dolls’ house and having the dolly vicar come to dolly tea. Of course. And frankly, I want this one.

Had she not been doing this in her hiding space under the stairs, she might have been playing with one of those astonishing dolls’ houses Victorian girls of the richer variety were given. Admittedly, these existed, so they claimed, specifically so that little girls could learn about domesticity and generally how to a house. Toys, after all, must have an educational value. I’m sure every rich little Victorian girl kept this very much in mind while rearranging the furniture in her dolls’ house and having the dolly vicar come to dolly tea. Of course. And frankly, I want this one.

There’s something about dolls’ houses. When they were little, I made my boys a great big one out of cardboard boxes. I had a few bits of tiny furniture from my own childhood (I confess to a tendency to hoard) and I made some stairs out of shaslick sticks, matches and thread. The boys brought out their dolls (commonly known as ‘models’ at the time) and so He Man and Skeletor sat in and wandered about the house, went upstairs to bed and came downstairs to breakfast. An eon or so ago I wrote about this in an article in Independent Australia: https://independentaustralia.net/life/life-display/children-at-play-the-war-on-pink,6031

But I digress by over a hundred years.

In 1860 Toby, Adelaide’s son, would no doubt have had a rocking horse, and maybe a Noah’s Ark, though in this he, too, was part of the exclusive set of the upper middle class.  Had he been a girl, he might had had a doll of porcelain so exquisitely dressed no child was allowed to touch it. I seem to remember in my distant youth that old ladies still had precious porcelain dolls sitting in a froth of lace on their beds. I would go in and stare at them, which was what you were meant to do. It was a bit like visiting a shrine.

Had he been a girl, he might had had a doll of porcelain so exquisitely dressed no child was allowed to touch it. I seem to remember in my distant youth that old ladies still had precious porcelain dolls sitting in a froth of lace on their beds. I would go in and stare at them, which was what you were meant to do. It was a bit like visiting a shrine.

As industrialisation moved on, cheaper toys came onto the market and more of the less filthy rich children were able to play with something other than sticks and knuckles. These new toys were mass-produced, often in Germany and often of tin. They could be mechanical as well. This was the age of the steam train, so clockwork railways were popular (not for girls. Don’t be silly). As were lead soldiers. There were drawbacks to lead toys, however, that Victorians were yet to discover – sucking them, as children would, was really not good for you.

These toy soldiers could be virtually flat and under a millimetre thick – which was a lot cheaper than the solid metal kind. They’d be balanced on a base so they could stand up to their full 3cm, or 4cm on horseback, and you could move them about to cries of ‘Charge!’ and ‘Bang bang boom’ to your little childish heart’s delight. The manufacture of rounded hollow soldiers had to wait until 1893, when William Britain invented them and ensured 300 figures an hour could be churned from a hand-held mould. You could buy forts and farms in which your little figures could move, but little boys would very likely invent their own setting at home, perhaps in the backyard or the street with lovely piles of dirt or stones. There was a variety of figures being manufactured: Soldiers, sailors, farmers, animals and carts were, of course, little boys’ toys.

In the second half of the nineteenth century wooden toys had largely given way to metal, though there was still room for the whittling uncle to impress the young, or indeed a range of simple toys (see below). America came into its own as toy manufacturer.

In the absence of home entertainment centres, TVs and computers, Victorians had to find something to do at night. So they played card games and board games, making their own if they couldn’t buy them. By Adelaide’s time, it seems the middle class (and the other classes well before them) had wearied of being instructed educationally through absolutely everything they did or played with, and cards became a matter for pleasure. Colour printing was now possible, making cards were attractive and popular for young and old. Still, a little instruction on how to be good was almost unavoidable, which is how we have had bequeathed to us games like ‘Happy Families’ and so on.  But there was also, by some point in the century, Snakes and Ladders, Ludo and Draughts, and children lucky enough to be allowed to play outside and with other children (perhaps overseen by Nanny, or grumpy Uncle Alfred, or, if working class, no-one at all) could disport themselves with hoops, marbles and skipping ropes. And there was always hopscotch.

But there was also, by some point in the century, Snakes and Ladders, Ludo and Draughts, and children lucky enough to be allowed to play outside and with other children (perhaps overseen by Nanny, or grumpy Uncle Alfred, or, if working class, no-one at all) could disport themselves with hoops, marbles and skipping ropes. And there was always hopscotch.

Of course there were complaints about kids getting underfoot in the street. Here’s a heartfelt one to The Times in 1842:

THE HOOP NUISANCE

Sir, – I have not for many years read a paragraph in The Times which has afforded me greater pleasure than that which heads your “Police” report of this day, conveying Mr. Hardwick’s just complaint of, and directions to Inspector Baker, on the hoop nuisance. As a daily passenger along the crowded thoroughfares of London-bridge and Thames-street, where boys and even girls, drive their hoops as deliberately as if upon a clear and open common, I can bear witness to its danger and inconvenience. I have at this moment a large scar on one of my shins, the legacy of a severe wound, which festered, and was very painful for an entire month, inflicted a year ago by the iron hoop of a whey-faced, cadaverous charity-boy from Tower-hill, who on my remonstrating with him on his carelessness, added impudence to the injury, by significantly advancing his extended fingers and thumb to his nose and scampering off. Aware that I had no redress, that the police would not interfere, I was compelled to grin and bear it while I hobbled away. The nuisance calls loudly for the interference of the Police Commissioners.

Your daily reader,

September 30. A PEDESTRIAN.

letter to The Times, October 1, 1842

As I keep saying, Victorians are so familiar to us.

You could also draw different pictures on either side of a disc or card, which is attached to two pieces of string. Twirl quickly, and it all spins around so suddenly that, say, the bird on one side of the card looks as though it’s actually in the cage drawn on the other. Minutes and minutes of harmless fun!

Some of these entertainments are viewable here, with descriptions on how to make them: https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/history/handsonhistory/victorians_games.pdf

If you weren’t keen on metal toys, or couldn’t afford them, or just liked fiddling with wood, it was quite possible to make was were called ‘automata’, little carved figures with very basic workings that went up and down or round and round with the aid of a handle. Then you could paint them, with lead-based paints, naturally, with much the same effect when sucked as the little lead soldiers would have had. Maybe they might not have sucked quite so much on the cup and ball – after all, this was all about hand-eye coordination—or the wooden pop gun. Once again, mainly for boys.

I am assured here:

http://chertseymuseum.org/domains/chertseymuseum.org.uk/local/media/images/medium/All_About_…_Victorian_Toys.pdf that spinning tops could be conjured out of all sorts of rubbish by poorer kids, though the more wealthy would have had some elaborate versions.

In the meantime, legislation eventually ensured that more children could read (and fewer sent down the mines), so there was a huge growth in children’s book industry. Beatrix Potter produced her still-popular books, all illustrated by herself, towards the end of the century. Of course, there was a lot of children’s literature that was dour and plain miserable, and lasted long enough on shelves to depress me hugely when I was reading my way through the British Council Library in Saigon in the 1960s.  But there was also Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass, both apparently so enchanting to Queen Victoria (who had many children) that she asked for ALL the books written by their author. It was disappointing to her, I understand, to discover that many of the books of Charles Dodgson (known to us as Lewis Carroll) were actually about mathematics.

But there was also Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass, both apparently so enchanting to Queen Victoria (who had many children) that she asked for ALL the books written by their author. It was disappointing to her, I understand, to discover that many of the books of Charles Dodgson (known to us as Lewis Carroll) were actually about mathematics.

When not reading, the bored child could cut out bits and pieces for scrap books.

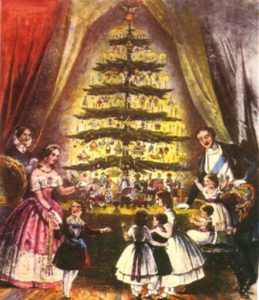

Christmas in 1860 was already decorated (at least in the houses of the better-off) with the Christmas tree, introduced to Britain by Prince Albert. They were all the rage in Germany, which, in turn, had picked up the habit from the area that is now Estonia and Latvia. There’s a story that Martin Luther was the first to place and light a candle on top of a fir tree, but I couldn’t swear to that one.  Branches from evergreens have long played a role in all sorts of cultures, of course. Anyway, Victorians were quite taken by the idea, as they were taken by any idea of the royal family’s. One of the presents at the foot of the tree could have been a real theatre in miniature. This would be bought from George Pollock’s shop in Hoxton, and would include changes of backdrops, wings, trapdoors, bridges and floaty fairies – quite possibly adapted from real productions. Cor!

Branches from evergreens have long played a role in all sorts of cultures, of course. Anyway, Victorians were quite taken by the idea, as they were taken by any idea of the royal family’s. One of the presents at the foot of the tree could have been a real theatre in miniature. This would be bought from George Pollock’s shop in Hoxton, and would include changes of backdrops, wings, trapdoors, bridges and floaty fairies – quite possibly adapted from real productions. Cor!

Alternatively, your child (from a wealthy family such as *Toby’s) could receive a magic lantern, which along with variations on such optical toys, such as the zoetrope, was a kind of precursor for the cinematograph. The latter was, essentially, a movie camera, of the type in use in a jerky kind of way from around the 1890s. I myself was partial to the kaleidoscope, which Victorian children also played with. It’s interesting how some ideas and concepts have lasted so well.

*yes, you’ll have to read the novel for the reference!